The Continental Divide Trail (CDT) unites us. From Gateway Community residents to thru-travelers, and everyone in between, our diverse community is connected by our mission to protect the CDT. We are showcasing stories of the people and places that make up our community with our series, Voices of the CDT. Each month, look out for new stories that highlight these diverse experiences, histories, and faces, against the backdrop of the awe-inspiring Continental Divide.

INTERESTED IN SHARING YOUR CONNECTION TO THESE LANDSCAPES? SEND US YOUR STORY AT [email protected] FOR A CHANCE TO BE FEATURED!

” The Father of the Continental Divide Trail”

This piece is an excerpt from our December 2018 edition of Passages. Passages is first available for members of CDTC.

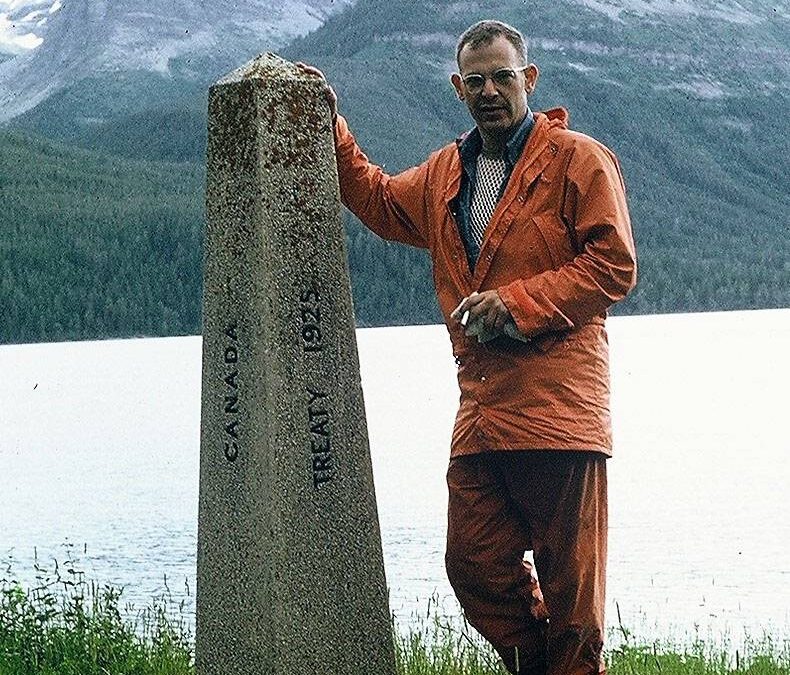

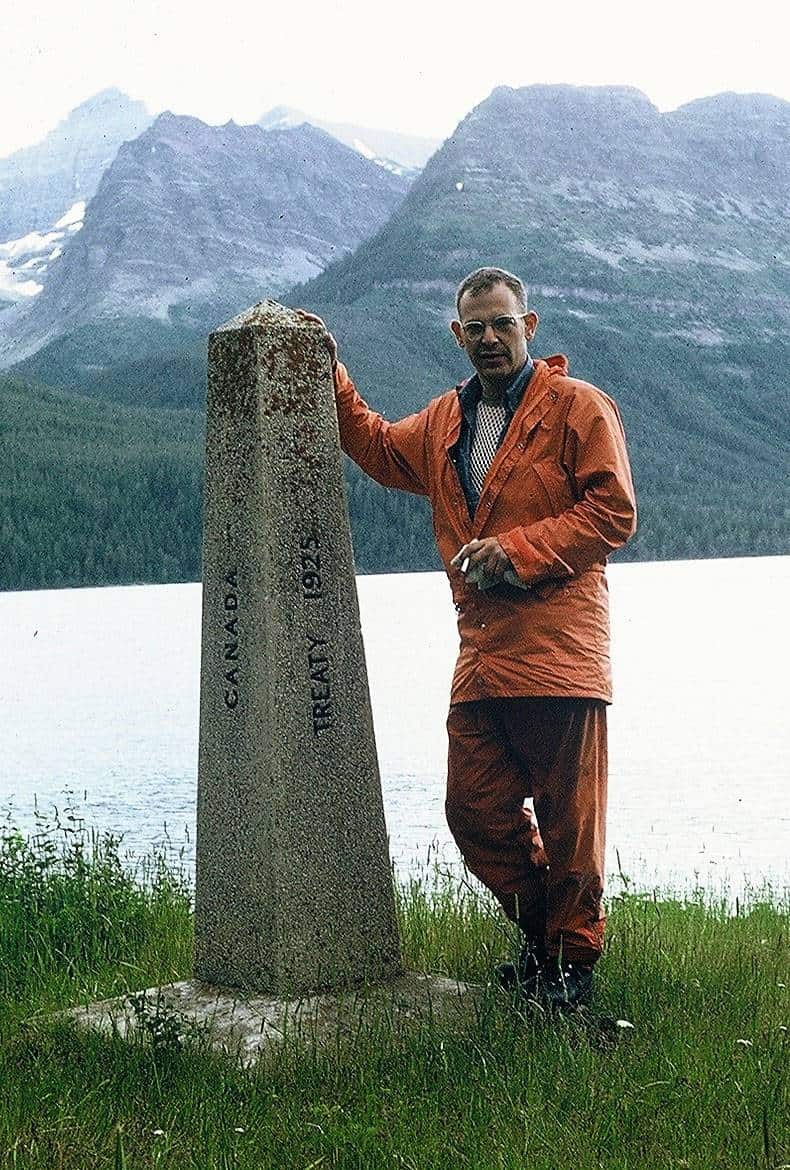

Jim Wolf knows the stories of the CDT and its evolution better than anyone, in no small part because he played an integral role in them. Known fondly as the “father of the Continental Divide Trail,” Wolf founded the Continental Divide Trail Society in 1978, and has dedicated much of the past four decades to the creation, improvement, and protection of the CDT. From testifying to Congress on behalf of the Trail to writing the first series of guidebooks for the Trail, Wolf’s contributions to the CDT are many. Earlier this fall, 40 years after the Trail was designated by Congress, CDTC Executive Director Teresa Martinez spoke with Wolf about his legacy.

Teresa Martinez: When did you first visit the Divide?

Jim Wolf: My first experience on the Divide was a summer trip, about 1965, with several friends from the Pittsburgh Climbers. We spent about a week in the Wind Rivers in Wyoming, in the Mt. Bonneville area, hiking and climbing.

TM: When did you first hear about or envision a trail traversing the Divide? How did you get involved with efforts to create the CDT?

JW: I don’t know when exactly, but I did think about it while I was hiking the AT in 1971. After completing the AT, I thought about the feasibility of a Continental Divide Trail. I consulted maps and tried to visualize possible routes. Next, I began planning an initial trip – and hiked from the Canadian border to Lincoln, MT, in 1973. As planned, I kept detailed notes of my trip. Those notes eventually became the first guidebook in the series I published with Mountain Press in Missoula.

TM: During the period before 1978, did you always have faith that the CDT would eventually be established, or was there the thought that Congress would decide it wasn’t worthy of National Scenic Trail designation? JW: I never feared that Congress would fail to find the CDT worthy of designation, mostly because I was not aware of ongoing efforts to consider the establishment of a Continental Divide Trail until 1976! But once I learned about the Congressional review, I traveled to D.C. to testify on behalf of the CDT before the House Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation. “And, most important, [the CDT hiker] will have developed an appreciation of his closeness to the land and his obligation to pass its treasures on to future generations.” Gannett Peak, in the Wind River Range, is Wyoming’s highest point at 13,810′.

TM: What was testifying in front of Congress like?

JW: It was actually a very pleasant experience. The Subcommittee chairman, Roy Taylor of North Carolina, was the only member of Congress present! I had a prepared statement with me, which I was assured would be placed in the record (and in fact it is in the published report). I then began my testimony by reference to my hike of the Appalachian Trail. I stated that it prompted me to “include an activity of hiking as an important part of my own personal development, and during the past three summers I have spent a great deal of time hiking in the West, specifically for the purpose of scouting the Continental Divide Trail… I was distressed perhaps by what I perceived to be the slow pace of activity under the Trails System Act, and it seemed to me that I perhaps could be of some assistance by taking some initiative and going out and seeing for myself what is there. During this period, I have hiked now from the Canadian border, essentially south to Rawlins, Wyoming, the southern part of Wyoming, leaving aside what I know is one of the most spectacular areas, the Bridger Wilderness, which I hope to complete this summer. So it is on the basis of very detailed experience that I can inform you that the Continental Divide Trail at least in the states of Montana, Idaho and Wyoming already exists. I think it is time and appropriate now for Congress to consider once again the designation of this outstanding pathway as a national scenic trail. I hope that my being here will help to lead in that direction.”

TM: Do you have a favorite place on the CDT?

JW: There are too many to pick just one! Some of my favorite places aren’t on the designated route. Of course there are the places everyone loves, like Glacier National Park and the Chinese Wall in the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana, or Cirque of the Towers and Green River to Island Lake in Wyoming. But some of my favorite areas are less famous – Henrys Lake in Montana, Elwood Pass to Blue Lake in Colorado’s South San Juan Wilderness, the Ignacio Chavez Wilderness Study Area in northwestern New Mexico, and the Florida Mountains, to name a few.

TM: Looking back over the past 40 years – what are the moments that feel the most significant? That you’re most proud of? That you never expected?

JW: Some of the most significant moments in my eyes have been the publication of the Trails for America report endorsing the designation of the CDT, the initial publication of Guide to the Continental Divide Trail in 1976, of course the official designation by Congress in 1978, the completion of a Comprehensive Plan for the CDNST in 1985, the dedication of Chief Joseph Pass in 1989, and the formation of the Continental Divide Trail Coalition in 2012. I have a lot of proud moments, the first of which is my appointment to and participation in the CDT Advisory Council and all of the opportunities I’ve had to support the CDT in public settings. There have also been many successful appeals to agency actions along the Trail, like prohibiting motorized vehicles on the Trail segment south of Monida, MT. I was also very proud when the Continental Divide Trail Society reached 200 members from all across the United States, Canada and Europe, and of course I’ve been very proud of the commendations made by hikers, organizational and agency officials, and others regarding our planning and management of the Trail and providing reliable information to the public. Most of all, I’m proud to be a spokesman for the CDT as a silent trail.

TM: What has been the most rewarding part of directing CDTS?

JW: Aside from all of the proud moments, some of the most rewarding aspects have been the friendships I’ve made with CDTS members as well as other trail leaders – especially through the Partnership for the National Trails System and the Continental Divide Trail Coalition. It’s also very rewarding to have a sense that in the years of my retirement, I have contributed to hikers’ enjoyment of high-quality scenic and primitive hiking opportunities, and helped with the conservation of natural and historic resources.

TM: What challenges did you anticipate, and which ones have taken you by surprise?

JW: One set of challenges, things we always knew would happen, arises from proposals to carry out projects that will interfere with the natural setting of the Trail because of visual or sonic intrusions. One example is the construction of a thousand-turbine wind farm on a mesa south of Rawlins, WY, about four miles east of the CDT, where many turbines will be in view from the Trail. This is proceeding despite our efforts to relocate the Trail farther west, where the turbines would be blocked from view by an intervening mountain. Other challenges which were harder to anticipate relate to the environmental impacts of climate change, such as early snowmelt which reduces water availability in summer and results in dry forests and fields. This combined with higher temperatures has increased the frequency and severity of fires, necessitating Trail reroutes, impacting scenery, and affecting water quality and wildlife.

TM: How do you envision the CDT in another 40 years?

JW: With sensible and effective policies and actions to control global warming, I believe the CDT can avail itself of its opportunities and attract long-distance and sectional hikers at many times their current numbers, enjoying scenic landscapes and weather conditions quite similar to what we have today. However, I do not discount the severity of likely environmental challenges that could so impact the Trail as to hurt its attractiveness and use.