The Continental Divide Trail (CDT) unites us. From Gateway Community residents to thru-travelers, and everyone in between, our diverse community is connected by our mission to protect the CDT. We are showcasing stories of the people and places that make up our community with our series, Voices of the CDT. Each month, look out for new stories that highlight these diverse experiences, histories, and faces, against the backdrop of the awe-inspiring Continental Divide.

INTERESTED IN SHARING YOUR CONNECTION TO THESE LANDSCAPES? SEND US YOUR STORY AT [email protected] FOR A CHANCE TO BE FEATURED!

Camp Lordsburg

A World War II prisoner of war and internment camp that held the U.S. Army’s largest population of first generation (Issei) Japanese internees.

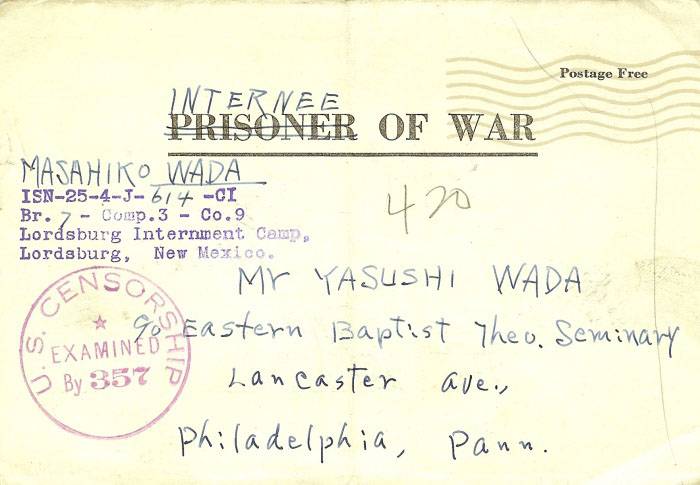

In February 1942, the U.S. Army began construction of an internment camp for Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants just outside of Lordsburg, New Mexico. By July of the same year, over 600 internees had been transferred from an internment facility in North Dakota to Camp Lordsburg. During the short period of construction, the Army had built 283 buildings, paved a road to Camp Lordsburg, and added electricity, water, telephone, sewage, and gas systems to the property six miles east of town.

Japanese internment camps were established through Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II. With this Executive Order, the War Relocation Authority was created in 1942 with the mission of taking people of Japanese ancestry into custody, preventing them from buying land, and returning them to their former homes after the war. Specifically, people of Japanese ancestry in designated zones along the Pacific Ocean (California, Oregon, Washington, and Hawaii) were targeted for internment camps. This Executive Order and the subsequent forced location to camps across the country led to the incarceration of approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, over two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens and many of whom were forced to abandon their businesses, farmlands, professions, and homes with little time to plan.

To arrive at Camp Lordsburg in New Mexico, detainees were dropped off by train and marched four miles through the desert to the camp. Camp Lordsburg became infamous in 1942 when two elderly Japanese American internees, Toshiro Kobata and Hirota Isomura, were shot and killed by a guard during this long walk for allegedly attempting to escape. Accounts of the incident since then have made it clear that the two men were struggling to keep up with the pace of the march and may have stopped to relieve themselves. Once at the camp, the detainees were forced to live in sparse barracks and remain in the camp’s area, enclosed by barbed wire fences and watched by guards.

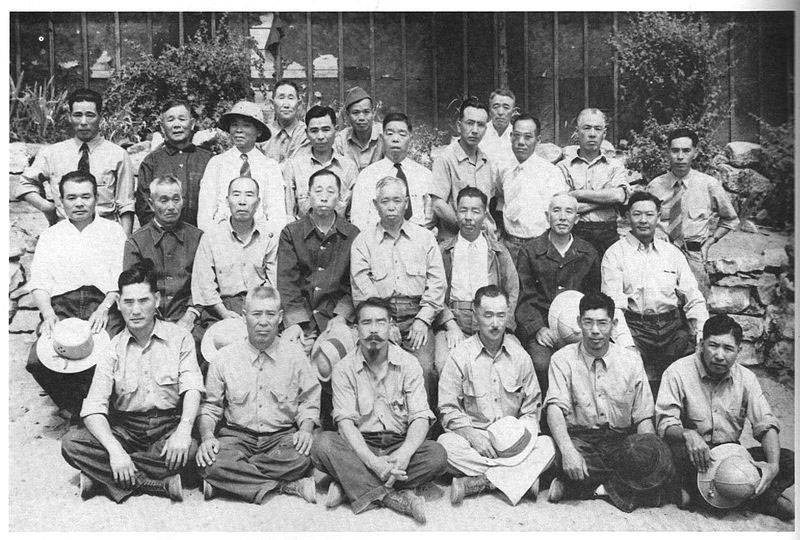

Life in Camp Lordsburg, though never comfortable, took on familiarity for the men who had been relocated. They established activity groups ranging from athletics to arts, including a Japanese literature group, painting groups, and religious services. The internees had a small shop where they could buy basic items and some also made small handicrafts to sell to the local Lordsburg community.

At the height of capacity, Camp Lordsburg held 1,500 Japanese internees — all men, mostly middle-aged or older. By 1943, the Japanese Americans were transferred to other locations, and almost 4,000 Italian prisoners of war, as well as many German prisoners of war, were brought to the re-designated Lordsburg Prisoner of War Camp until it closed in early 1946. While at Camp Lordsburg, the Italian prisoners were known to work on ranches up to 50 miles away during the day. After the war, a number of Italian men stayed in New Mexico and sent for their families in Italy. Numerous Japanese-American families also stayed in New Mexico after being released.

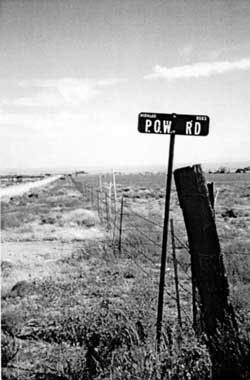

Camp Lordsburg was decommissioned in late 1946. Shortly after, all the buildings were auctioned and removed and the property was sold to private owners. It wasn’t until 1988 that President Reagan signed a law requiring the U.S. Government to repay each detained individual $20,000. Today, the only remnants that remain of Camp Lordsburg are the commissary safe, a replicated seal of the U.S. Army made by detainees, and a few signs in the area.

While the property where Camp Lordsburg once was is now privately owned, you can visit the Lordsburg-Hidalgo County Museum to learn more and view a searchlight from one of the guard towers, drawings of the camp, and a representation of the barracks.

To read more about Camp Lordsburg, please visit these additional resources: Densho Encyclopedia, National Park Service – Park Net, National Japanese American Historical Society, National Archives – Japanese American Internment, New Mexico Japanese American Citizens League, or the Lordsburg-Hidalgo County Museum.

Special thanks to Dean Link from the Lordsburg-Hidalgo County Museum for sharing resources and infromation.