by Barney Scout Mann

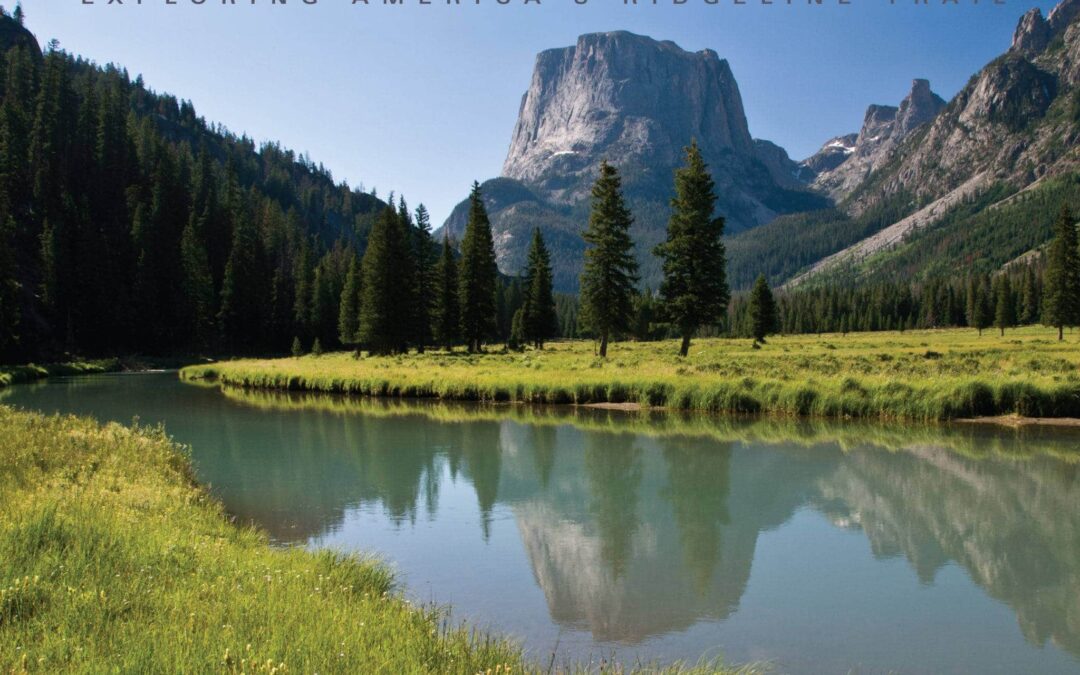

The newest addition to Rizzoli’s bestselling trail series, The Continental Divide Trail: Experiencing America’s Ridgeline Trail features breathtaking images and inspiring stories from the CDT. Celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Trail, the book is now available in bookstores and online. Proceeds benefit the Continental Divide Trail Coalition.

The following excerpt is taken from Chapter 6: Trailblazers.

“I was never lost. Lost is a four-letter word. Occasionally I was temporarily disoriented,” said Mary Stuever. One time during her five months on the CDT, Stuever was “temporarily disoriented” for three days.

Born in Albuquerque but raised in Oklahoma City, Stuever had always favored New Mexico’s mountains over the flat Oklahoma plains. She was 11 when her parents discovered backpacking. It was the 1970s, the era of external-frame packs and Colin Fletcher. Stuever was 14 when she and her mother went on a backpack trip in northern New Mexico. It was stormy, and the sky flung hail like buckshot. But the clouds broke open, and the sun struck brilliant blue alpine forget-me-nots growing above tree line. “I want to stay up here the rest of my life,” Stuever breathlessly told her mom. “Maybe you should hike the Continental Divide,” her mother replied. Stuever said from that moment on the idea obsessed her.

She planned to start hiking the summer of 1977 right after graduating high school. Stuever’s enthusiasm was infectious, and a friend caught the Divide bug. They started buying USGS maps and making plans. But then her friend decided to get married instead. “It was a blessing,” Stuever said. “We didn’t really have a clue what we were doing.”

Stuever went to Oklahoma State University and majored in forestry. The Divide was never far from her mind. She spent summers leading backpacking trips. She was on staff at a summer camp in Maine and a Boy Scout camp in New Mexico. It’s no small deal to be a backcountry ranger at Philmont Scout Ranch in the New Mexico high country. In 1981, Stuever spent the entire month of January trekking with HikaNation. It was a yearlong, coast-to-coast trek sponsored by the American Hiking Society. The goal was to bring more attention to long-distance trails.

Three months later, she stood at the Mexican border looking north. Her long hair was tied in a tight braid as she hefted a pack scuffed with trail cred. She wore a T-shirt she’d designed and sold to raise money for her trek. The front read “Hike the Great Divide” and featured her dreamed-of mountains. Even as she took her first steps, Stuever’s trek was already unique for three firsts.

One was her hiking companion. Stuever was the first thru-hiker to set out with a dog. A black Catahoula hound dog, Jarrett was short haired and flop eared, always sweet with Stuever, but he looked intimidating when he glared. “He was an incredible partner,” she said.

She was also the first to cut a deal with the Forest Service to scout a CDT route. The contract was for her first state, New Mexico. Years later, crowdsourced data from hikers became relatively common. But in 1981, Stuever was a crowd source of one. As an official volunteer, the Forest Service provided her with free maps and a stipend of $8 per day.

Last, Stuever was earning 13 units of college credit. She was writing an undergraduate thesis about the trek. The very idea must have amused Jim Wolf of the Continental Divide Trail Society. In his August 1981 DIVIDEnds newsletter, he told his readers about her college credit arrangement and then ended with, “Her dog, Jarrett, is also making the trip, but isn’t getting any credit.”

The Daily Oklahoman planned a series of articles on her progress. When Stuever started on March 13, 1981, the newspaper’s headline read, “City Woman Leaving Today to Hike Continental Divide.” The reporter described her gear and food and then mentioned one other thing she carried—“a pocketful of courage.”

She needed that pocketful early. Not even two weeks had passed when her left foot swelled up. “It was the size of a watermelon,” she said. She was so concerned she went off trail to Albuquerque to have it X-rayed. Three weeks later, she had it X-rayed again after reaching the Colorado border. Both times the doctors said they didn’t see anything wrong.

Stuever was buoyed by the generosity of those she met when she brushed civilization. Walking on a road or in a town, it wasn’t unusual to be offered a place to stay or a meal. “In New Mexico, it felt like every other night someone opened their home to me,” she said.

One day in Colorado, Stuever went from one high ridge to the next, not realizing she was off the Divide. A few moments’ lapse is all it takes, and the CDT can slap you in the face. Stuever walked off the edge of her map. That night, she went to sleep not knowing where she was. It was the same the next night. After three days of being temporarily disoriented, she saw a shape in the distance. “Is that a rock cairn?” she thought. All the while climbing toward it, she kept hoping that humans, not nature, had piled the rocks and that it meant she’d find a trail. Finally, when she stood alongside the piled mound, she saw a faint trail leading north. She was back on track. She made a promise right there. “When I have a daughter,” she thought, “I will name her Cairn.”

In the 120-mile expanse of Wyoming’s Great Divide Basin, huge “Thumper” trucks were exploring for oil and gas, pounding the ground, and taking seismic measurements. Instead of 20 miles or more between water sources, Stuever was offered water multiple times a day.

In northern Wyoming, however, coming out of the Wind River Range, she saw a sign for a new danger she’d never heard of—giardia. The signs were oriented for southbound hikers. The bug was in the streams behind her, the ones she’d been drinking from for days. When her mom met her at a trailhead campground, Stuever was sick in her tent, wracked with vomiting and diarrhea. The local emergency room was overrun. There were so many giardia-stricken patients that Stuever had to sit on the floor. While there, she also had her painful foot X-rayed for the fourth time, but doctors still didn’t see anything wrong.

When she hiked into Yellowstone National Park, she and Jarrett had walked 2,000 miles. It should have been time for an early celebration, but as she hiked through the ancient caldera, past steam vents and active bubbling mud pots, her left foot flared up the worst of the whole trip. “I practically crawled into Old Faithful,” she said. She left Jarrett and her gear in West Yellowstone with a kindly bookstore owner. Stuever flew home to Oklahoma City and saw a sports medicine specialist. He took her fifth set of X-rays, but used a different angle. “Two ankle bones are fusing. If you hike out now, you’ll never be able to hike again,” he said. She was crushed. She had to quit the trail.

After 1981, the CDT never faded from her life. Stuever gave birth to her first child on October 10, 1984, and fulfilled the promise she’d made to herself. Her daughter was named Cairn. Every time Stuever used her daughter’s name, it reminded her of the moment she went from being “disoriented” to found.

Unfortunately, Stuever’s life took a tragic turn. On Valentine’s Day, four months after she was born, Cairn was found dead in her crib. SIDS, or sudden infant death syndrome, is a parent’s worst nightmare. Today, on the lip of the Rio Grande River Gorge, there is a solitary rock cairn where Stuever scattered Cairn’s ashes. Every time nature and the elements tear it down, Stuever rebuilds it. She visits every year.

Stuever made much of her college degree, forging a career in forestry and timber management. Since 2010, she has been a district forester for the state of New Mexico. More than 450,000 acres of private and state timberland in the northern part of the state fall under her purview. Stuever has also been active as a volunteer. She serves as the liaison between Chama, New Mexico, an official CDT Gateway Community, and the Continental Divide Trail Coalition.

Stuever said a great lesson from her 1981 trek was how good people can be. So it’s not surprising that she recently posted this entry on the Philmont Scout Ranch website: “In early summer and early fall, my guest room often has strangers staying there. They are generally good people—hikers on the Continental Divide Trail. My neighbors think I am nuts. ‘Why do you let people you don’t know in your home?’ My answer: to pay off a karmic debt. Thirty-six years ago, while I was hiking the Divide, I was shown so much kindness by strangers that I’ll always keep paying it forward.”

Barney Scout Mann is a CDTC board member and Continental Divide Trail thru-hiker. This is the second book he has authored on long-distance trails.