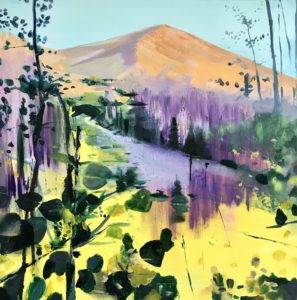

This piece is an excerpt from our December 2021 edition of Passages. Passages is first available for members of CDTC. Find Annie Varnot’s painting, sculptures, and other works, including commissions, on her Instagram and website. Above: Vespertine Desert, 40×30”, oil on canvas, 2020.

Artist Annie Varnot has learned how to be in two places at once, and two people at once.

The versatile painter and sculptor, whose paintings in oil and watercolor are evocative, while also familiar and inviting, has long worked to capture the grandeur of the landscapes of the American West, particularly along the National Scenic Trails.

Her work, as her life, has been a challenge in uniting seemingly contradictory spheres. Born in rural Massachusetts to a forester/math teacher mother and a father with a long list of outdoor occupations, her childhood was spent equally outdoors and in. “My parents would erect an army tent in the back, and my sisters and I would move all our bedroom furniture outside to sleep all summer,” Varnot says. Their home was dotted with apple orchards, pick-your-own strawberries, a sugar shack, an apiary, pumpkin and squash patches with produce sold out of the family truck, and there was always another job to be done, no matter the season.

Yet even as she learned and grew amid the familial whirlwind, part of her longed for stillness and a quiet, calm space of her own. “I always had this compulsion to make things look nice, designing and organizing things as a means of trying to control the chaos in my surroundings,” Varnot says. Amid the bustle of her household, she found painting to be a place of respite at the eye of the storm. “I would just be working on an art project amid the tall stacks of my mothers’ math class papers at the dining room table, completely absorbed.” In painting, she found the canvas to be a space all of her own imagination and control. “By age 15, I knew that’s what I wanted to do for the rest of my life,” she says.

During her undergraduate studies, Varnot continued to inhabit two worlds, dressing in gothic and eccentric clothes as she pursued a studio art degree, and switching to athletic wear for her spot on the downhill ski team. Despite her wide-ranging interests, Varnot found that the pursuit of a contemporary art career and enjoyment of the outdoors could be mutually exclusive. After a skiing accident broke her hand, inhibiting her work, a drawing professor told her that she would have to choose between athletics and art.

She chose art.

But that choice came with a price tag. When her original plans to pursue a Masters degree in art seemed hampered after some rejections from graduate programs, she felt deflated, moving west to pursue solo work in a more scenic environment in California. But even as the mountainous scenery enthralled her, she felt isolated and afraid of showing her work to others. “The more I refrained from showing people my work, the more my work suffered and I suffered mentally,” she says. She reapplied to graduate programs, and returned east to earn a Master’s degree in painting at U-Mass: Amherst. Upon graduating, she moved between fellowships and adjunct teaching positions before moving to New York City to follow the dream of becoming a successful contemporary artist in the hub of the visual arts industry. Varnot primarily sculpted for nearly two decades. But the furor of urban living took its own toll. “I started to have panic attacks and an extreme reaction to the environment and the lack of nature. I reacted to it in a way I didn’t expect,” Varnot says. While she eventually acclimated (“humans are so capable of adapting to difficult situations”), there was still part of her that felt discontent in the intense urban landscape.

Starting in 2005, a series of personal crises took their toll on Varnot too, and upended the life track she had been planning for herself. In the span of the next six years, she was diagnosed with cancer, married, suffered a miscarriage, and divorced. (“How do you address these difficult subjects in art?” she asks.)

While Varnot was living on an air mattress in her studio in 2011, feeling listless and unmoored, a friend asked her if she would like to come hike the first section of the Pacific Crest Trail together. She impulsively jumped at the chance, and it became a pivot in the direction of her life.

She had five weeks to spend before she was scheduled to start an art residency in Wyoming, and though she had a few backpacking trips under her belt at the time, she threw herself into the PCT with arms wide open. It took no time at all for trail to feel like home. “I was so hooked! I had a hard time leaving after five weeks, and I knew I had to get back to [the PCT],” she says.

While on this section hike, she tried to find ways to incorporate the rhythms and motions of backpacking into her art. “We were using Halfmile’s topo maps in 2011, and I started drawing on the maps and writing notes. When I returned to the studio, I asked, ‘How do I make art about this?’ I was taking components from the map and superimposing my hike, doing watercolors, collage, pencil and pen, symbols of my experience during a day on the trail.” While she had been on the PCT, she would sometimes ask someone important in her life to send her a map of their day in return. This gave her another lens to view the relationship between urban life and backcountry, a theme she continues to explore. “Someone’s day in the city is much more geometric and linear, and a map of a day on trail is curvilinear and organic. I was so interested in these shapes and how they communicate,” Varnot says.

But for future hikes, Varnot decided not to set creative expectations on her experience, but rather decided to be present and open to whatever the journey brought her way. On her PCT thruhike in 2017, a record snow season in the Sierra Nevada Mountains created terrifying mountaineering challenges. Her watercolor journal disappeared somewhere in the mountains. She continued to take photos and journal. And in the backcountry of Washington, everything changed.

“I had a profound spiritual experience,” she says. “I wasn’t experiencing verbal language anymore. I was boundaryless between myself and my surroundings. It dawned on me that the best way to communicate my experience was through painting.” Varnot hadn’t painted seriously since school, but felt a powerful pull towards the medium. “There’s a history of using landscape painting [to explore] how we experience nature and what nature means to us as a species. Why not use a modality that already has a visual language established that can be used to explore my connections with nature?” Contemporary art discourse had previously warned her off painting, as there was a pervasive sense that avant garde and impactful art was being created exclusively in different media, and that painting was too thoroughly explored to be culturally challenging. She decided to stop listening to that internal criticism.

Upon returning to New York, she posted up in a neighbor’s apartment with borrowed easels and a canvas, flipping through her photos and journals from trail to bring herself back to specific places and feelings from her hikes. She’s hardly stopped since — occasionally just to hit the trail again. She’s since hiked several thousand miles across National Scenic Trails, including the Continental Divide Trail in 2019.

And in capturing National Scenic Trails in art, she’s found the bridge between athletics and art. “Painting for me is very similar to hiking. It’s a journey. I don’t know what’s going to come out and I don’t know what’s ahead of me, so there’s this experience of travel without moving. The idea of home for me is more of an experience than a place. The trail is home and painting is home. There’s this contentment in being present in the moment,” she says.

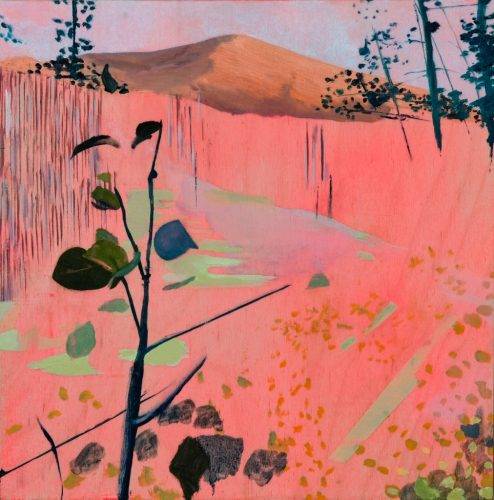

FROM LEFT: Continental Divide Trail, Colorado: Descending Hope Pass, oil on birch panel, 12’“x12”, 2019. Continental Divide Trail, Colorado: Fleeting 1, oil on birch panel, 12’“x12”, 2019. Continental Divide Trail, Colorado: Fleeting 2, oil on birch panel, 12’“x12”, 2019. https://www.redfoxartgallery.com/product-page/annie-varnot-continental-divide-trail-colorado-fleeting-2

By the time her CDT thruhike came around, Varnot was experiencing trail differently, imagining paintings even as she traveled, seeing moments as she would hope to capture them later. “One memorable experience for me was at the top of Hope Pass,” she says. “It was fall, and the aspens were changing and moving. The color was divine, alpine sunset, my favorite time in the universe. I get so elated at dusk, and getting up the pass was so challenging, and I remember having that sensation of not wanting to take a step forward because then that moment is in the past and the place is in the past.” She was enchanted by “the idea of translating that experience into painting, having that love in a place where you don’t want to let it go, but then it’s already gone.”

That moment on Hope Pass became her first series of paintings after the CDT, called Fleeting. She’s since captured several other moments from trail, and hopes to continue working on more in the near future, particularly the New Mexican desert. “I love the dusk in the desert, and how going through the desert during the day, it feels like you’re the only thing moving, and at dusk it all comes alive,” she says.

And Varnot has become comfortable with embracing all aspects of her self and personality and voice, without having to pigeonhole herself into one arena. She’s planning new paintings of the San Juan mountains, as well as artistic explorations of climate change and extreme weather in the West.

As Varnot continues to wander between studio and trail, she has warm encouragement for other artists who may want to explore the National Scenic Trails. “If you don’t have an idea for a project, just surrender completely to the hiking experience and be completely present to your surroundings and the people you meet. Trust that you will get inspired. Because you will.”

— Allie Ghaman | CDTC Communications Manager