by Andrea Kurth

This article was originally published in CDT Passages, CDTC’s e-magazine. To receive Passages in your inbox three times a year, become a CDTC member today.

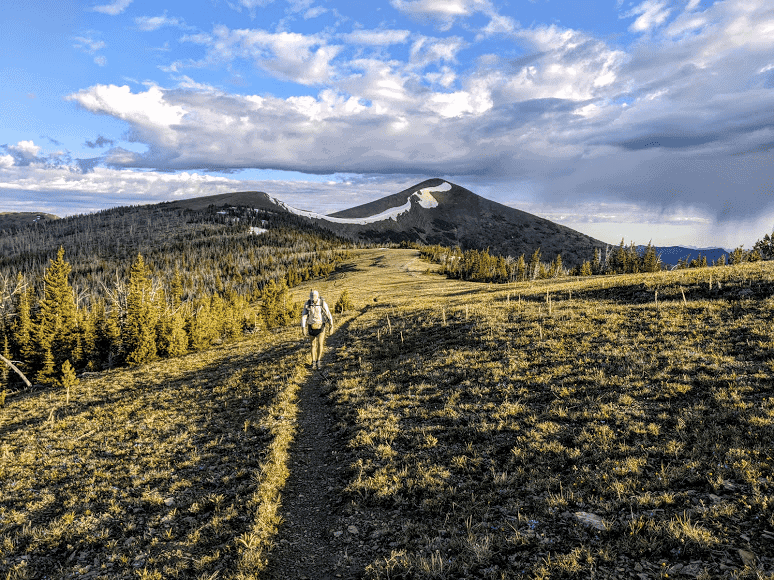

The CDTC is much more than just a line on a map, and constant changes due to reroutes, new construction, and closures of old sections quickly render data collected in years past obsolete. In 2019, CDTC partnered with Atlas Guides, makers of the popular Guthook Guides hiking apps, to create a new volunteer role and collect data about the CDT. Last June, Dahn Pratt set off on a southbound hike, capturing GPS data, photos, and waypoints along the way as CDTC’s first ever Atlas Guides Data Fellow. We talked to him about his hike, data collection, and why maps are important for the longevity of trails.

How long have you been long-distance hiking?

I started hiking in 2014 – I did the Appalachian Trail with my then-girlfriend and her Alaskan Malamut. Then I did a bit of international traveling for two years. I ended up in Japan and started working like a Japanese salary man and got really sick of it. I daydreamed about what I would do if I wasn’t limited by 60 to 70-hour work weeks, so I started creating a bucket list of places I wanted to go like the Wind River Range in Wyoming or Patagonia. It wasn’t good enough to daydream about all the places I wanted to go, so I started planning fictious hikes that connected all the places I was dreaming about. Then that wasn’t enough, so I decided just to go for it and do a 10,000-mile hike that connected all the places on my bucket list. I’ve been seriously hiking since the end of 2017, with the intended goal of doing 10,000 miles.

How did you get connected with Atlas Guides?

As I was planning this very ostentatious trip, I realized I couldn’t afford to do it. I started reaching out to different companies that might be interested in with working with me to test gear or gather data. I was basically willing to work while I walked to live this dream. I reached out to Atlas Guides and told them about my crazy idea. I’m sure they get approached a lot by people who want to gather data, but they took a liking to my plan for some reason. They told me the apps for the trails in my plan were either in development or are going to be released soon, so it was a perfect opportunity to gather data for them. It was a good way to give back to the trail community while financing my trip in small part.

On which trails have you collected data?

The Continental Divide Trail, along with the Te Araroa in New Zealand, the Pacific Crest Trail, and a trail in the Middle East comprised of the Jordan trail and Israel National Trail.

How does the partnership between Atlas Guides and CDTC work? What happens after the data is collected?

When I was out hiking on the CDT, I thought would collect this data in the field and then just pass it along to Atlas Guides, and that’s where my fellowship would end. In January, I was offered a position by Atlas Guides and have been cleaning some of the CDT data that I collected. It’s really fun to be on both ends of the geographical spectrum of creating this data – both in the field and back at home. I get to relive my hike and make the needed changes to the data. It’s the best office experience I could hope for – if I’m going to be looking at a computer all day, at least I get to look at data that I have a connection to.

Atlas Guides and CDTC are trying to make the best possible on-the-ground reality of the trail come to life in a digital format. We worked with the CDTC to establish which alternates I’d be taking, based on the popularity of certain routes. The CDT is kind of like a “choose your own adventure.” I didn’t do the authoritative line – I did the alternate through the Wind River High Route and the Middle Fork of the Gila River. After the collection, we took all the data from Atlas Guides, CDTC, and the Forest Service, and tried to make the most accurate line for the trail. I collected about 4,500 waypoints, some new and some updated, which gives us a better image of what the trail looks like in digital format.

What does data collection entail? What kind of gear did you need?

Most people don’t know I’m collecting data while I’m hiking because it doesn’t affect my behavior too much. I look like a normal hiker, stopping and looking at my phone or taking a picture every once in a while. The data collection is done all on automatically, which is very convenient. Atlas Guides created an Android app that I was using to capture data. Whenever there was a point of interest along the trail, I would take a picture of it and create a waypoint in the app. It wasn’t a lot of work, but it takes a lot of battery power for my phone to be constantly pinging 23 satellites. Normally, people carry 1 or 2 power banks with them, but I would carry 3 or 4, plus a solar charger. I had to be very cognizant about my battery consumption. I was only using my phone for data collection – I would hardly use it for anything else because collecting data drained so much battery.

What makes the CDT different from other trails you’ve collected data on?

It’s the longest trail I’ve ever done and longest trail I’ve ever collected data on. It’s a big project but it’s also one of the more remote backcountry experiences I’ve ever been on – this added a layer of excitement and a bit of dread in a positive way. The CDT was a litmus test of my backcountry skills and my mental capacity because it’s very challenging.

How did volunteering to collect data on the CDT make your thru-hike different from others you encountered on the trail?

One of the biggest things was that I took being a steward of the trail more seriously when I became a data fellow. I felt very connected to the CDTC and like more of a steward and an ambassador for trail communities and hikers. It made me more cognizant of how hikers are perceived, and I thought more about how we are guests not only in the wilderness but also in the communities we pass through. I thought overall, it made me a better person because it held me to a higher level of ethical obligation. I took Leave No Trace principles more seriously and I wasn’t as likely to cut corners – I had to elevate Leave No Trace because I was part of the team!

How will the data points you’ve collected be used by CDTC?

So far, we’ve sent a completely updated center line and alternates to Slide Kelly, the GIS Program Manager at CDTC. He wanted a clearer picture of where hikers are going. There’s a Forest Service line that goes from Mexico to Canada, but if everyone is hiking a different path, then in reality, the trail is much more nuanced than it is on the map. The data I sent to CDTC was an updated spreadsheet of all the waypoints that I gathered, water sources, points of interest, campsites, and other points. The trail is constantly changing – not just in its path but in what the topography does to the trail. One year, a water source might be a river, and another year it might be a dry creek bed. Or, that change can happen as quickly as in a month. Having the most current data points helps people to have the best experience possible on the trail.

Why is it important to keep the data current?

Maps are so important because they give people the tools to access trails. If the data isn’t up to date, then people are disincentivized to use trails and they fall into disrepair. It only takes 5-7 years for nature to reclaim a trail if it’s not maintained. If we don’t know where people are hiking, then we run the risk of losing what we worked so hard to create over the past 40 years.

What do you wish other trail users knew about what goes into making navigational aids?

Having worked on both sides of the screen – both collecting and processing the data – I want people to understand the sheer amount of work and hours that go into making navigational aids. There’s hardly any automation possible for Geographic Information Systems, so a lot of this work is done by hand or in a spreadsheet. It really is a labor of love and I’m so impressed by Atlas Guides and CDTC. The number of hours that go into bringing a map to life is really hard to comprehend.

How did you feel when finishing the CDT? We know you achieved the Triple Crown of Hiking (thru-hikes of the CDT, Pacific Crest Trail, and Appalachian Trail). Did the added component of data collection enhance your experience of finishing the trail?

I was relieved to finish because I had some serious doubts about whether I was capable of finishing – the trail was really good at testing my resolve. Having the data to gather helped keep me accountable to continuing. Having a mandate like that was helpful to motivate me and to make me think of it as an accomplishment that was larger than a selfish adventure. I was happy to benefit others than just myself.

Andrea Kurth is CDTC’s Gateway Community Program Manager. When not exploring the amazing public lands near her home in Leadville, she enjoys exploring the intricacies of high-altitude baking.